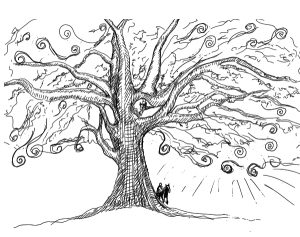

Aliso del Viento

El Aliso del Viento sprung from the tumultuous floodplain of the Los Angeles River as Christopher Columbus arrived in the Americas. This sycamore seedling flourished as the Chumash and Tongva peoples sought peace and guidance. When El Aliso del Viento’s canopy spanned over 200 feet wide, the Tongva people created the Yaanga village around this sacred refuge. In 1781, new settlers choose land next to the Yaanga village to establish El Pueblo de la Reina de Los Angeles, and when the Tongva relocated Yaanga village, the settlers turned to El Aliso del Viento for shade and as a landmark to their rapidly growing city. El Aliso del Viento watched as El Pueblo de la Reina de Los Angeles gained cityhood as the City of Los Angeles in 1850. The town of 44 settlers became a city of 50,000 in less than a hundred years, and in turn, these new residents privatized and sold El Aliso del Viento. After 300 years serving as a spiritual landmark for the region, El Aliso del Viento witnessed the growth of the agricultural industry while proving shade for citrus farmer’s newly constructed home. The next owner created a winery with the surrounding land, but felt El Aliso del Viento was too big and not worth restoring to health as the centerpiece of his winery. El Aliso del Viento was chopped down in 1892, after years of neglect mirroring the changing values and spiritual practices of the people using the land.

On the cusp of cityhood in 1849, the roads, plots of land, fences, the river and the Zanja Madre of El Pueblo de Los Angeles were inked into memory. The Zanja Madre, meaning Mother Ditch, was the first attempt to control the wild Los Angeles river. The settlers of El Pueblo de la Reina de Los Angeles created the open, earthen ditch within a month of settling the area to divert the river water to the center of town, on present-day Olvera Street. As the town attracted more settlers and developed more agricultural fields, the demand for water grew as faster than the Zanja Madre could provide. Brick and mortar were used in 1884 to make the Zanja Madre keep up with the settlers, as if cementing the ditch would make the water flow faster, better, greater. However by the early 1900s when the population had doubled to over 100,000 residents within ten years, the settlers understood the futility of their actions. Floods continually wrecked the Zanja Madre’s waterwheel, the demand for water could not be satiated and so the city leaders retreated the town’s dependence on the Zanja Madre and searched for another source. In 1908, the city began construction on their solution, the Los Angeles Aqueduct system, and William Mulholland leads the path as chief engineer to force water along a 233 miles journey south from the Owens River to the city of Los Angeles in an open concrete canal. Over $20 million dollars poured into the creation of this concrete waterway and the Los Angeles Aqueduct opened in 1913. During this time, the Los Angeles River continued to be as it always had. Powerful, unpredictable floods continued to damage the man-made structures and agricultural fields. After the flood of 1938 took over 100 lives, the citizens demanded for the river to be under greater control. With time, the solution again used concrete. The life of the river was cut off for nine months in the 1950s and then reopened under the city’s terms. As a result, the river became entombed and useless for the people. The life source of the land became drained from its purpose so others may profit and feel safe within an artificial landscape.

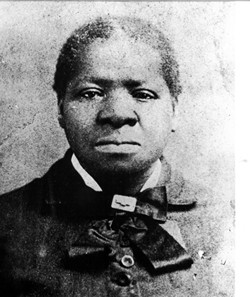

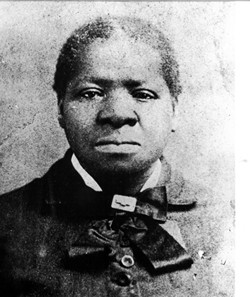

William J. Seymour and Biddy Mason

Biddy Mason was Los Angeles’s first philanthropist. Born a slave on a Mississippi plantation in 1818, Mason’s life was fraught with hardships, but her driven spirit led to gaining her freedom and relocating to Los Angeles in 1856. Within ten years of working as a midwife, Mason saved enough money to purchase property on Spring Street for $250, thereby becoming one of the first African-American women to own land in Los Angeles. Mason sold part of the property in 1884 for $1,500, and over the years, her wise business and real estate transactions enabled her to accumulate a fortune of almost $300,000. Becoming the first philanthropist in Los Angeles, Mason gave generously to charities, visited jail inmates, and provided food and shelter for the poor of all races. Her faith fueled her philanthropy, and within one of her properties, 312 Azusa Street, a global spiritual movement began. In April of 1906, African American preacher William J. Seymour preached his first sermon at 312 Azusa Street and the Azusa Street Revival began. From 1906 to 1909 at this site, Seymour preached peaceful co-existence and charismata (gifts of the Spirit), giving birth to the Pentecostal movement which currently has over 500 million followers worldwide. In addition, Mason’s generosity gave birth to the church now called the First African Methodist Episcopal Church. Beginning as a bible study at Mason’s home on Spring Street in 1872, the congregation continued to grow and relocated within downtown Los Angeles, using 312 Azusa Street from 1872 to 1888 and currently located seven miles away at 2270 South Harvard Boulevard. First African Methodist Episcopal Church has continued Mason’s mission, being the “first to serve” and providing social services to downtown communities.

Tab 4

Internment camps and repatriation

During the 1930s, tens of thousands, and possibly more than 400,000, Mexicans and Mexican-Americans were pressured — through raids and job denials — to leave the United States during the Depression after the stock market crashed in 1929. This deportation was enforced without due process. Officials staged well-publicized raids in public places. For example, on Feb. 26, 1931, immigration officials suddenly closed off La Placita, a square near Olvera Street and about 1.4 miles north of Azusa Street, and questioned the roughly 400 people there about their legal status. With time, Mexican-Americans were granted repatriation, but in the 1940s with the outbreak of the Pacific War, all people of Japanese descent living on the West Coast were removed from their homes, had their properties and businesses seized, and incarcerated. Half a mile from Azusa Street, the Nishi Hongwanji Buddhist Temple in Little Tokyo became a roundup point for the Japanese Americans who were sent to “assembly centers.” From March to August in 1942, over 92,000 Japanese-Americans were booked at these “assembly centers” and transported to internment camps. These two travesties share two common themes. First, their cultural meeting spaces were used against them, defiling the peaceful, community-building activities which take place at La Placita and Little Tokyo. And secondly, the train became a recurrent force of removal, as both groups were forcibly relocated and stripped of their rights by the symbol of mobility, progress and development.

Tab 5

Grapefruit Tree

On December 8, 2012 at the corner of Azusa Street and San Pedro Avenue, a ceremony to remember united the Japanese Americans, Azusa Street Pentecostals, Skid Row, and Native Americans communities. The last remaining citrus tree from the old agricultural fields had passed away in 2006 at the ripe age of 125 years old due to an accident in the bustling downtown streets. The tree was beloved by the local community, who still ate its fruit; and in the tree’s passing, the community came together. To commemorate the tree that several communities cherished, a new tree was planted in its place through a planting ceremony. Inviting everyone to participate by adding a scoop of soil to the newly planted grapefruit tree, the community recommitted to the tradition of natural landmarks: to allow a new tree to be witness to the growing city and to come together in the spirit of peaceful coexistence under the tree’s shade.