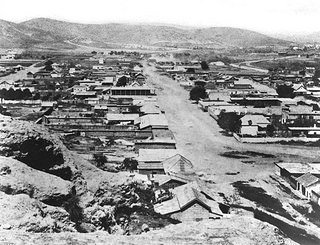

Sonoratown, an early neighborhood

The neighborhood of “Sonoratown” acquired its name during the years of California’s gold rush, when a wave of miners and other migrants from the Mexican province of Sonora settled there.

Drawn originally to Northern California’s Gold Country, the Sonoran 49ers introduced several innovations, including the panning method, and quickly established themselves as some of the state’s most successful prospectors. Beginning in 1848, when a ban on immigration from northern Mexico was lifted, thousands of Sonorans passed through Los Angeles every year on their way to the Gold Country. Others came to work on Southern California’s vast cattle ranches, which supplied the booming northern counties with meat. In 1851 alone, approximately 8,000 Sonorans passed through Los Angeles, then a town of only 1,600.

But with the wounds of the recent Mexican War still fresh, a peaceful coexistence between the Mexican miners and their American counterparts was unlikely; by 1850, most Sonorans had been evicted from their mining claims. Many returned to Mexico, but a significant minority lingered in Southern California, where the footprint of Anglo culture was still faint. Sonoratowns quickly sprang up across the region, from Santa Barbara to San Diego. (Despite the name, Sonorans were not the only denizens of the region’s Sonoratowns; Anglo-Americans then used the terms “Sonoran” and “Mexican” interchangeably, and immigrants from East Asia, South America, and Europe also called the Sonoratowns home.)

In Los Angeles, the erstwhile miners settled in the area north of the city’s old plaza, where native, Spanish-speaking Angelenos still occupied aging adobes dating from the city’s Spanish and Mexican periods. The housing was generally either old adobe structures or “housing courts,” which were ramshackle structures built around a central area. They generally consisted of two rooms. A kitchen, typically six by 10 feet had a small wood-burning stove and a table. The other room usually had a bed and a chair. The buildings were made of pine, whitewashed on the inside and painted either brown or red on the outside, and each room had one window. There was no plumbing, and residents shared a common outhouse. Lighting was by candles.

Sonoratown became a vibrant if destitute Mexican community. Life in the house courts and crumbling adobes may not have been comfortable, but residents there preserved remnants of the city’s original Latin American culture. Among white Angeleños, meanwhile, the neighborhood developed a reputation as a rough part of town, where “every evening there was much indulgence in drinking, smoking and gambling,” as Harris Newmark put it. Cockfights were common, according to Newmark, and many saloons doubled as brothels.

In the late nineteenth century, even as white Angeleños scorned Sonoratown as a slum, tourists discovered it as a place to commune with Southern California’s Spanish past. The publication of Helen Hunt Jackson’s 1884 pastoral novel Ramona introduced Americans to a romantic reimagining of Southern California’s history. In the ensuing years, many of Jackson’s readers came to Sonoratown in search that Spanish fantasy past—never mind that most Sonoratown residents arrived after the American conquest.

J. Torrey Connor was among the pilgrims. In her 1902 travelogue, Saunterings in Summerland, Connor wrote: “Among the households of Sonoratown may still be found those who remember the days when the flag of the Mexican republic floated over the pueblo. La Senora [de la Reina de Los Angeles] is bowed beneath the weight of years, but she has not forgotten how she danced in the moonlight under the golden-fruited orange trees, to the trilling of mandolins, and well she recalls how, with a glance from her bright eyes, she brought the gay caballero to her feet.”

The image on the left is of Sonoratown in 1869.